Jebel Rimhan was once a complete obsession of a mountain for me. It struck me the first time I saw it; more than any other peak in the Sinai. I was on my way to Jebel Umm Shomer and it was there in the dawn; its huge, twin peaks rising in the morning haze; each a perfect pyramid. Behind it, the Hejaz lined the horizon along the coast of Arabia. I saw it from a lot of other places after that. And wherever it appeared – from whatever angle – it looked just as beautiful; just as majestic. Jebel Rimhan is one of the Sinai’s biggest peaks at 2437m; but unlike other big peaks here – like Umm Shomer, Thebt and Serbal – it didn’t have an established route on it, which just added to the allure.

Jebel Rimhan was once a complete obsession of a mountain for me. It struck me the first time I saw it; more than any other peak in the Sinai. I was on my way to Jebel Umm Shomer and it was there in the dawn; its huge, twin peaks rising in the morning haze; each a perfect pyramid. Behind it, the Hejaz lined the horizon along the coast of Arabia. I saw it from a lot of other places after that. And wherever it appeared – from whatever angle – it looked just as beautiful; just as majestic. Jebel Rimhan is one of the Sinai’s biggest peaks at 2437m; but unlike other big peaks here – like Umm Shomer, Thebt and Serbal – it didn’t have an established route on it, which just added to the allure.

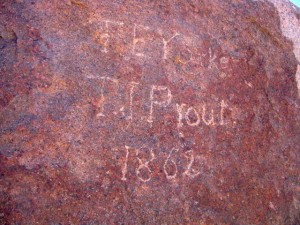

The first – and only – recorded ascent I know of was made nearly 100 years ago, by George W Murray, a highland Scot who worked on the British Survey of Egypt.

Talking about recorded anythings is always dubious in a place like Sinai, whose people were historically one of the spoken word, never putting anything on paper. But Murray had climbed mountains all over the Sinai, he knew the Bedouin well and – even then – reckoned the ‘maiden pikes of Rimhan, the Two Lances’ were unscaled; either in recorded or unrecorded terms.

Whatever the story, he didn’t go with a local Bedouin. He went with a Bedouin from the mountains of mainland Egypt – Ali Kheir – who found the way from scratch. Murray found it such a tough route to follow that – as a mark of gratitude and respect – he bought his guide the best cross-handled sword he could find when they got back to Cairo; a prized relic from the Battle of Omdurman.

Unfortunately, Murray didn’t record specifics of the route they did that day.

I spent years asking around, trying to find someone who knew the way. There were plenty of folks who reckoned they knew it; but none of them were ever available. I gave it the first go in winter of 2012 with a Bedouin guide called Auda; an ageing talkaholic in white plimsolls and a baggy coat down to his knees. I’d walked with him before – to Jebel Umm Shomer – and found it totally exhausting. Not the walk. All the talking. I like silence in the mountains. I don’t like to talk; or even think through language.

I spent years asking around, trying to find someone who knew the way. There were plenty of folks who reckoned they knew it; but none of them were ever available. I gave it the first go in winter of 2012 with a Bedouin guide called Auda; an ageing talkaholic in white plimsolls and a baggy coat down to his knees. I’d walked with him before – to Jebel Umm Shomer – and found it totally exhausting. Not the walk. All the talking. I like silence in the mountains. I don’t like to talk; or even think through language.

I just like to exist. To see stuff. To feel things.

Auda was the enemy of silence itself. When he couldn’t think of anything to say, he’d just whoop, or scream. He’d be a challenge on a par with the mountain itself but if he knew the way – and he said he did – it was a fair price to pay.

Half way up he stopped on a high promontory, leant back in a limbo like pose and bellowed up at the sky – with a celebratory edge – ‘MAFEESH TAREEEEEEEEEEG! Which was to say, no way. He was right too. A huge ravine sliced the mountain in half. Getting down into it wasn’t the only problem. We’d have to climb out the other side onto the summit section; a mass of smooth, bulging granite, towering up hundreds of metres. The whole thing looked frightening. Cracks, cuts and black lines ran through the crags, like scars on an ancient face. Jebel Rimhan was like a giant’s head, sleeping and ready to wake.

Auda didn’t seem bothered. He just stood there, bellowing.

Walking back that day felt like a failure; I kept turning round, wanting to go back. Looking at the mountain; thinking we should have tried the last crags. That we should’ve been bolder or braver. Or found another way. That we should have gambled. That we should have just done it without thinking. For weeks afterwards – when I went back to downtown Cairo – I saw Jebel Rimhan when I closed my eyes; like its twin peaks had been photographically exposed on my retina. They appeared in the darkness, like a silhouette; the specks and phosphenes floating over them.

Walking back that day felt like a failure; I kept turning round, wanting to go back. Looking at the mountain; thinking we should have tried the last crags. That we should’ve been bolder or braver. Or found another way. That we should have gambled. That we should have just done it without thinking. For weeks afterwards – when I went back to downtown Cairo – I saw Jebel Rimhan when I closed my eyes; like its twin peaks had been photographically exposed on my retina. They appeared in the darkness, like a silhouette; the specks and phosphenes floating over them.

It was a year before I got another chance to do it; going back in 2013. And the second time was even more of an unmitigated failure than the first, ending when I thought my guide was having a heart attack after the first pass.

He wasn’t – hamduleleh – but something wasn’t right. So we bailed.

On the way back we met a local Bedouin who said he’d been up. He was an elderly guy called Salem who set a princely sum for guiding me, which I paid only to avoid having to break the news of another failure back in town.

We made a dawn raid, shooting straight for the summit on a dragon’s back type ridge. The Sinai doesn’t have many ridges; not like the glaciated ranges of Europe, with their knife edge arêtes and cirques. Occasionally, a geological quirk creates one in the landscape though; and most of the time, they’re gems. This was one of the best; bristling with high fins of rock you had to weave between all the way along. About half way up the ridge, the summit suddenly appeared. I got a sudden burst of hope, thinking we’d do it; third time lucky. Further up though, Salem sat down on a rock and got his binoculars out; an ominous sign.

We made a dawn raid, shooting straight for the summit on a dragon’s back type ridge. The Sinai doesn’t have many ridges; not like the glaciated ranges of Europe, with their knife edge arêtes and cirques. Occasionally, a geological quirk creates one in the landscape though; and most of the time, they’re gems. This was one of the best; bristling with high fins of rock you had to weave between all the way along. About half way up the ridge, the summit suddenly appeared. I got a sudden burst of hope, thinking we’d do it; third time lucky. Further up though, Salem sat down on a rock and got his binoculars out; an ominous sign.

We could see an impenetrable looking thimble of crags at the end.

We went up to look. Sure enough though; they were too high, too tricky and serious for a pair of scramblers – looking for a scrambler’s route up – like us. We’d got higher than ever. Just below the top. We weren’t there; but it wasn’t totally wasted. Getting this far showed us the peak we’d been centering on – the northerly one of the twin peaks – wasn’t actually the highest.

As it transpired, Salem didn’t know the way up Jebel Rimhan. He’d said he did, gambling and hoping it’d unfold as we got up.

And all that talk is a big part of Jebel Rimhan for me. Down in the towns; in the tents, by the fires, where everything’s comortable and everybody can just talk without ever showing anything for it, people know the way. Everyone’s an expert. Press them on the specifics though – especially when you’ve been on the mountain – and you’ll see it’s all totally empty. It mirrors the way mountain knowledge is getting moth eaten across the Sinai too. Bedouin knowledge – hard won by earlier generations – is gradually being forgotten. And knowledge of the mountain tops is the worst hit; it’s been the first to go of everything on the peninsula.

And all that talk is a big part of Jebel Rimhan for me. Down in the towns; in the tents, by the fires, where everything’s comortable and everybody can just talk without ever showing anything for it, people know the way. Everyone’s an expert. Press them on the specifics though – especially when you’ve been on the mountain – and you’ll see it’s all totally empty. It mirrors the way mountain knowledge is getting moth eaten across the Sinai too. Bedouin knowledge – hard won by earlier generations – is gradually being forgotten. And knowledge of the mountain tops is the worst hit; it’s been the first to go of everything on the peninsula.

It’s partly because the Bedouin inhabit a new, modern world in which mountain knowledge is irrelevant. They don’t need it any more. Especially nothing about the high mountain tops. Why would they? Wadis are still highways in the mountains; so they still get talked about. They’re still better known.

In some ways, the empty, feigned knowledge about Jebel Rimhan is sad to me.

As much as it’s a charade born from bravado, I think it’s born from a feeling they should know the mountains better. Especially in front of an outsider; I think it’s born of a feeling that something precious has been lost. And that they’re the generation that lost it; that they’re responsible the knowledge that set them aside from anybody else; the knowledge that made them Bedouin – rather than anything else – is waning. And it’s waning on their watch.

Anyway, after that third time, I gave up on people who said they knew the way.

I went back again in summer 2014 with a guy called Salem Abu Ramadan; the fittest Bedouin I know; and one of the best climbers and routefinders. We began early, heading for the higher peak; the one we’d spotted from the last attempt. I didn’t have high hopes; it looked even harder than the other. I was just there because I couldn’t rest easy until I’d tried everything I could on Jebel Rimhan.

We spent the morning creeping round the mountain like a pair of assassins trying to get into a forbidden castle. We started up a ravine that ended in a cul de sac. After that, we tried smaller gully with a rojom – a trail marking stone – in it. It was the first rojom I’d seen on Jebel Rimhan. A a sure sign someone had been here before. Maybe it was an old route marker. We followed it, then found a line of them that ended below a high, sheer wall we couldn’t pass.

We spent the morning creeping round the mountain like a pair of assassins trying to get into a forbidden castle. We started up a ravine that ended in a cul de sac. After that, we tried smaller gully with a rojom – a trail marking stone – in it. It was the first rojom I’d seen on Jebel Rimhan. A a sure sign someone had been here before. Maybe it was an old route marker. We followed it, then found a line of them that ended below a high, sheer wall we couldn’t pass.

We were running out of options. The last chance we had was a ravine that we’d avoided in the morning because a huge boulder was wedged half way up, blocking it. But we gave it a go: there was nothing else.

Getting round the block turned out easy. Big views soon unlocked over the landscape as we got higher and the towering crags soon began to taper off. At the end of the ravine we scrambled onto a ridge.

We looked left, and there it was. The summit. No big crags. No big obstacles.

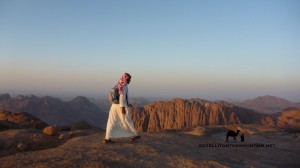

The ridge – flanked by massive drops – ran up to it. We followed it along – crossing a few wobbly boulders, one of which groaned like it was about to plunge off – to reach the top. It felt lik hallowed ground. Finally, after all the years, we were there. We could see the other peak – the object of our three failures – and behind it Jebel Umm Shomer. The Sinai unfolded all around, looking beautiful. Where it ended, the summits of Africa stood up across the sea; with the mountains of Arabia on the other. It was one of the most spectacular sights I’d seen in the Sinai; almost as beautiful as the twin peaks of Jebel Rimhan itself. As much as it felt good to be on the top, part of me felt sad the story was over. That there wouldn’t be another mountain like it.

The ridge – flanked by massive drops – ran up to it. We followed it along – crossing a few wobbly boulders, one of which groaned like it was about to plunge off – to reach the top. It felt lik hallowed ground. Finally, after all the years, we were there. We could see the other peak – the object of our three failures – and behind it Jebel Umm Shomer. The Sinai unfolded all around, looking beautiful. Where it ended, the summits of Africa stood up across the sea; with the mountains of Arabia on the other. It was one of the most spectacular sights I’d seen in the Sinai; almost as beautiful as the twin peaks of Jebel Rimhan itself. As much as it felt good to be on the top, part of me felt sad the story was over. That there wouldn’t be another mountain like it.

Not such an epic, forgotten and mysterious a peak as Jebel Rimhan.

The best thing about doing it wasn’t getting there. It was finding a good way up. A way anybody could do. It was winning back that lost knowledge about one of the Sinai’s biggest, most beautiful peaks. Jebel Rimhan is a sleeping giant of a peak; I hope this route we did might begin to make it wake because this is a mountain that deserves a place alongside the Sinai’s other great summits.

If you want to try the mountain, I can guarantee this guy knows the way, as we went together. Salem Abu Ramadan: 0101-497-6289.

This blog is mostly about mountains. I love getting to the tops of mountains. I love how they represent the last point between the earth and the sky; the last place we can go and the most natural end to a journey we could ever make. If there’s a single moment though – a single, iconic moment – that rivals getting to the top of a mountain, it’s arriving in an oasis. And I mean arriving in an oasis after days in the desert. When you get to an oasis, suddenly, there’s shade. Suddenly there’s water. You can hear the birds. You can smell the fires. You get handed tea. It’s that moment of knowing you’re out of the wilderness; that, just for a moment, there’s sanctuary and you can breathe easy.

This blog is mostly about mountains. I love getting to the tops of mountains. I love how they represent the last point between the earth and the sky; the last place we can go and the most natural end to a journey we could ever make. If there’s a single moment though – a single, iconic moment – that rivals getting to the top of a mountain, it’s arriving in an oasis. And I mean arriving in an oasis after days in the desert. When you get to an oasis, suddenly, there’s shade. Suddenly there’s water. You can hear the birds. You can smell the fires. You get handed tea. It’s that moment of knowing you’re out of the wilderness; that, just for a moment, there’s sanctuary and you can breathe easy. 1. EIN HAYALLA My favourite of all, I first spotted this from high on Jebel Madsus; far below, it looked like an emerald gem buried in the red rocks. It’s a cluster of green palms in one of the heads of Wadi Kabrin, with deep water pools and trickling creeks. There are bamboo tunnels and fallen tree trunks you can walk across like bridges. Long ago, this oasis was on a pilgrim route to St Katherine; you can still find Byzantine pottery and crucifixes etched on the rocks. One amazing way to walk here is via Wadi Hebran, from the coast. There’s a similarly spectacular route via Wadi Sig, but it’s longer. And harder. You can also walk in via a place called Baghabugh, from St Katherine.

1. EIN HAYALLA My favourite of all, I first spotted this from high on Jebel Madsus; far below, it looked like an emerald gem buried in the red rocks. It’s a cluster of green palms in one of the heads of Wadi Kabrin, with deep water pools and trickling creeks. There are bamboo tunnels and fallen tree trunks you can walk across like bridges. Long ago, this oasis was on a pilgrim route to St Katherine; you can still find Byzantine pottery and crucifixes etched on the rocks. One amazing way to walk here is via Wadi Hebran, from the coast. There’s a similarly spectacular route via Wadi Sig, but it’s longer. And harder. You can also walk in via a place called Baghabugh, from St Katherine. 2. EIN SHEFALLA You won’t find many folks who’ve been here. Half way up a deserted wadi that drains El Gardood – a high, foreboding plateau that flanks the Gulf of Aqaba – it’s just a couple of palms below a vertical cliff. It’s not the lush jungle of Ein Hayalla. But the surroundings are much harsher. And that’s why this little patch of green means so much here. It has a themila too: a hole where you can dig down to find water. Walking to Ein Shefalla isn’t easy. You can do it from Wadi Guseib, on the Gulf of Aqaba coast near Bir Sweir. It involves a tough hike over a hard-to-navigate plateau for which, like all the oases here, you’ll need an experienced Bedouin guide.

2. EIN SHEFALLA You won’t find many folks who’ve been here. Half way up a deserted wadi that drains El Gardood – a high, foreboding plateau that flanks the Gulf of Aqaba – it’s just a couple of palms below a vertical cliff. It’s not the lush jungle of Ein Hayalla. But the surroundings are much harsher. And that’s why this little patch of green means so much here. It has a themila too: a hole where you can dig down to find water. Walking to Ein Shefalla isn’t easy. You can do it from Wadi Guseib, on the Gulf of Aqaba coast near Bir Sweir. It involves a tough hike over a hard-to-navigate plateau for which, like all the oases here, you’ll need an experienced Bedouin guide. 3 EIN GUSEIB This little oasis huddles at the end of a rugged coastal wadi, below the El Gardood plateau. It’s a haven of green with palm trees, bamboo, pools and creeks that run through the sands. It’s a beautiful spot that you can get to with a walk from the beach. From Bir Sweir on the Gulf of Aqaba coast – roughly 25km north of Nuweiba – follow Wadi Guseib inland from the beach. Otherwise, you can do it at the end of a longer trail passing three of the oases here. Start near Ras Shetan and from here walk to Moiyet Melha (see below). After this you can climb up the El Gardood plateau, crossing it to Ein Shefalla and down its rugged coastal cliffs to Ein Guseib and the Gulf of Aqaba.

3 EIN GUSEIB This little oasis huddles at the end of a rugged coastal wadi, below the El Gardood plateau. It’s a haven of green with palm trees, bamboo, pools and creeks that run through the sands. It’s a beautiful spot that you can get to with a walk from the beach. From Bir Sweir on the Gulf of Aqaba coast – roughly 25km north of Nuweiba – follow Wadi Guseib inland from the beach. Otherwise, you can do it at the end of a longer trail passing three of the oases here. Start near Ras Shetan and from here walk to Moiyet Melha (see below). After this you can climb up the El Gardood plateau, crossing it to Ein Shefalla and down its rugged coastal cliffs to Ein Guseib and the Gulf of Aqaba. 4 MOIYET EL MELHA They say a ghoola – a sort of evil witch – guards this oasis, maiming or killing anybody who traps its animals, cuts its trees or tries to claim the oasis for himself. Some are scared of her; others see her as a benevolent force of nature. A guardian who protects its animals and trees against human greed. Moiyet el Melha is a long line of green palms that grow at the bottom of high cliffs, where water seeps out. Getting here isn’t too tricky: it’s at the end of a long coastal wadi called Wadi Melha, which starts near the beach camps of Ras Shetan. Half way along is Wadi Wishwashi, a spectacular ravine. The oasis is near the end of the wadi; a beautiful spot to sleep.

4 MOIYET EL MELHA They say a ghoola – a sort of evil witch – guards this oasis, maiming or killing anybody who traps its animals, cuts its trees or tries to claim the oasis for himself. Some are scared of her; others see her as a benevolent force of nature. A guardian who protects its animals and trees against human greed. Moiyet el Melha is a long line of green palms that grow at the bottom of high cliffs, where water seeps out. Getting here isn’t too tricky: it’s at the end of a long coastal wadi called Wadi Melha, which starts near the beach camps of Ras Shetan. Half way along is Wadi Wishwashi, a spectacular ravine. The oasis is near the end of the wadi; a beautiful spot to sleep. 5 EIN KIDD The only oasis in this list where you’ll find people. Sometimes, I like having places to myself. Other times, people add something. After days in the wilderness, it can be good to talk again. At least, it can with the right people. Getting stuck in an oasis with the wrong people would be a problem. Ein Kidd is in the territory of the Muzeina tribe and the Bedouin here are hospitable in the old school traditions. The oasis itself is a cluster of palms in Wadi Kidd, a long wadi that connects the St Katherine region with the coastal ranges. It’s a sort of half way house on treks between St Katherine and Sharm and it can also be tied into longer treks from the Jebel Umm Shomer area.

5 EIN KIDD The only oasis in this list where you’ll find people. Sometimes, I like having places to myself. Other times, people add something. After days in the wilderness, it can be good to talk again. At least, it can with the right people. Getting stuck in an oasis with the wrong people would be a problem. Ein Kidd is in the territory of the Muzeina tribe and the Bedouin here are hospitable in the old school traditions. The oasis itself is a cluster of palms in Wadi Kidd, a long wadi that connects the St Katherine region with the coastal ranges. It’s a sort of half way house on treks between St Katherine and Sharm and it can also be tied into longer treks from the Jebel Umm Shomer area.