THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN EGYPTIAN STREETS. Check out their website HERE and like their Facebook page HERE!

When it comes to mountains and the Middle East, a few countries might spring to mind. There’s Yemen, with its pretty mountain villages and the highest peak of the Arabian peninsula; Oman too, home to the mighty Al Hajar range. In the wider Arab world, there’s Morocco, with the high, snowy peaks of the Atlas. Egypt has mountains too – lots of them – but it’s not famous for them in the same way other countries are. Few outsiders see Egypt as a mountain country. And mountains aren’t really part of the image Egyptians project about their country to the world either; they’re not woven into the national identity like the Nile, or even the sweeping deserts along its banks. Mount Sinai might be famous; but it’s a single peak. Beyond this and perhaps a couple of other iconic summits the mountains of Egypt are little-known; much less actually visited.

When it comes to mountains and the Middle East, a few countries might spring to mind. There’s Yemen, with its pretty mountain villages and the highest peak of the Arabian peninsula; Oman too, home to the mighty Al Hajar range. In the wider Arab world, there’s Morocco, with the high, snowy peaks of the Atlas. Egypt has mountains too – lots of them – but it’s not famous for them in the same way other countries are. Few outsiders see Egypt as a mountain country. And mountains aren’t really part of the image Egyptians project about their country to the world either; they’re not woven into the national identity like the Nile, or even the sweeping deserts along its banks. Mount Sinai might be famous; but it’s a single peak. Beyond this and perhaps a couple of other iconic summits the mountains of Egypt are little-known; much less actually visited.

The mountains of mainland Egypt are amazing; on the Libyan side of the Nile, there’s Jebel Uweinat; on the other, the Red Sea Mountains.

But perhaps the most amazing of all are those of the Sinai.

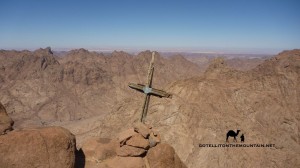

The Sinai is Egypt’s great mountain land; a rugged wilderness where peaks tower up to gaze over the Red Sea to Africa and Asia. Egypt’s highest mountains are found here. But it’s not the height alone that makes them special. They’re some of the world’s most fabled mountains; the setting for ancient Biblical legends that are still told today. And there’s the history too; relics from the times of the Pharaohs – and even more distant eras – are still scattered by old paths.

I took my first hike in the Sinai over six years ago now.

Like most would-be hikers, I started out on a familiar path; doing the best known peaks at the beginning. I did Mount Sinai first – the most written about, talked about, and easily the most-climbed peak anywhere on the peninsula – and then Jebel Katherina, whose main claim to fame is being Egypt’s highest mountain. After that, I moved on to the sort of peaks that aren’t very well-known outside the Sinai – but which are still well-trodden within it – like Jebel Abbas Pasha, which has an unfinished Ottoman palace on top, and Jebel Umm Shomer, Egypt’s second highest mountain. After those, I began moving further out to the more rarely visited areas, seeking out the most little-trodden peaks.

Like most would-be hikers, I started out on a familiar path; doing the best known peaks at the beginning. I did Mount Sinai first – the most written about, talked about, and easily the most-climbed peak anywhere on the peninsula – and then Jebel Katherina, whose main claim to fame is being Egypt’s highest mountain. After that, I moved on to the sort of peaks that aren’t very well-known outside the Sinai – but which are still well-trodden within it – like Jebel Abbas Pasha, which has an unfinished Ottoman palace on top, and Jebel Umm Shomer, Egypt’s second highest mountain. After those, I began moving further out to the more rarely visited areas, seeking out the most little-trodden peaks.

Whether you walk a famous or a lesser-known peak, the Sinai’s rarely easy.

Good paths are hard to come by. There are virtually no signposts. Nor easy, end-of-the-day conveniences. The infrastructure for hiking tourism just hasn’t been widely built up. Good maps are pretty much non-existent. And whilst it’s good for some areas in the Sinai, Google Earth doesn’t cut it for navigating intricate mountain routes. As much as anything, there’s a dearth of information – good written information – about many parts of the Sinai’s mountains.

Sometimes, you can delve back into the travelogues of European explorers.

They might be old, but they’re usually still useful. These explorers walked more widely than any contemporary author; and a lot of the time their records are the only ones available for parts of the Sinai.

Amongst these early explorers was Jean Louis Burckhardt, who won immortal fame for unveiling Petra to the West. He travelled through the Sinai in 1816, walking widely and climbing a few iconic mountains.

There was Edward Henry Palmer too; a Cambridge professor who wrote a remarkable travelogue featuring many little-known parts of the Sinai.

And George Murray; a highland Scot and born mountain man who climbed some of the Sinai’s hardest peaks; and others across Egypt.

Of course though, these explorers didn’t go everywhere. Or record everything.

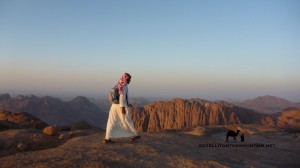

For large areas of the Sinai, there are still no written records. No modern ones; or older ones. Walking in these areas – in the most little documented parts of the Sinai – is a process that beings simply by asking questions. Specifically, by asking questions of the local Bedouin. The Bedouin arrived in the Sinai from the Arabian Peninsula centuries ago and walked the mountains widely from the start, looking for water, food, grazing and other essentials they needed to survive. They built up a huge bank of knowledge about its mountains through the ages. They were the Sinai explorers par excellence and their knowledge is still the only source of information available about a lot of the peninsula. When European explorers came to the Sinai they only ever explored it through the Bedouin, even if the Bedouin didn’t feature much in their written accounts. They had Bedouin guides; and they recorded Bedouin knowledge.

For large areas of the Sinai, there are still no written records. No modern ones; or older ones. Walking in these areas – in the most little documented parts of the Sinai – is a process that beings simply by asking questions. Specifically, by asking questions of the local Bedouin. The Bedouin arrived in the Sinai from the Arabian Peninsula centuries ago and walked the mountains widely from the start, looking for water, food, grazing and other essentials they needed to survive. They built up a huge bank of knowledge about its mountains through the ages. They were the Sinai explorers par excellence and their knowledge is still the only source of information available about a lot of the peninsula. When European explorers came to the Sinai they only ever explored it through the Bedouin, even if the Bedouin didn’t feature much in their written accounts. They had Bedouin guides; and they recorded Bedouin knowledge.

But Bedouin knowledge isn’t what it once was. Lifestyles have changed.

Today, many Bedouin have left the mountains for new towns and villages on their fringes. Knowledge about the mountains – once central to survival – is largely irrelevant now. And because it’s not used, a lot of it’s being forgotten.

You can see clear gaps in the knowledge of younger Bedouin already.

It’s the older Bedouin who know the Sinai best. But even then, tracking down the ones who know the ways up the hardest, most little-trodden peaks is a challenge. Sometimes, it can be simpler to just re-discover the routes from scratch.

This dearth of good written information about the little-known peaks of the Sinai is a hindrance to anybody wanting to do them. And to the development of hiking generally. I still experience it today. And it’s something I’ve tried to address through several projects. Earlier this year, I finished a trekking guidebook to the Sinai, published in the UK. It gives the best, most classic walks in the peninsula and the practical information needed to organise them.

More lately I created the website Go Tell It on the Mountain.

This is a project with a more specific mountain focus. And one which aims to start a grassroots documentation process. To begin a simple list of peaks – from the most famous to the most little-known – that will grow into a bigger bank of information that can be used to go deeper and discover more.

But it’s not just about showing what mountains are in the Sinai.

It records a more personal journey that I hope might help change perceptions about the peninsula. Over the last few years there has been a near constant stream of bad news from the Sinai; most of it from the North. But all too often North Sinai has been conflated with South Sinai; the peninsula portrayed as an undivided, unvariegated whole. Sinai is just Sinai. In reality the two areas have big geographical and social divides and South Sinai – which is where the mountains are – has been largely peaceful. Along with the bad press, Western governments have issued travel warnings for South Sinai, which have only reinforced perceptions of it as a place of danger. And even when warnings have been lifted for South Sinai resorts like Sharm they have remained in place for the mountains. The official message has been clear for years – don’t go.

It records a more personal journey that I hope might help change perceptions about the peninsula. Over the last few years there has been a near constant stream of bad news from the Sinai; most of it from the North. But all too often North Sinai has been conflated with South Sinai; the peninsula portrayed as an undivided, unvariegated whole. Sinai is just Sinai. In reality the two areas have big geographical and social divides and South Sinai – which is where the mountains are – has been largely peaceful. Along with the bad press, Western governments have issued travel warnings for South Sinai, which have only reinforced perceptions of it as a place of danger. And even when warnings have been lifted for South Sinai resorts like Sharm they have remained in place for the mountains. The official message has been clear for years – don’t go.

It’s a state of affairs that has undermined the tourism upon which many local communities have grown to depend. Many are seriously struggling.

This website is about creating a counter-narrative to the bad news.

It’s about putting an alternative voice out there and showing a more real, everyday side to the mountains. It’s about telling stories that show these mountains are home to an ancient Arab culture built on honour and hospitality to travellers. And that these traditions still hold strong today. Ultimately, it’s about showing that you can travel safely here – even in the most little-visited parts of South Sinai’s mountains – despite what they say.

My biggest hope is that tourism will return; and not just to those parts of the Sinai that had it before. But to the most little-trodden mountain areas.

The Bedouin have always supplemented traditional livelihoods by guiding travellers in their lands; from traders to pilgrims and early explorers. Mountain tourism like hiking – which has proved so successful in other Arab countries – would be a sort of modern re-incarnation of that, creating a type of work that plays to natural Bedouin strengths in a way the Sinai’s glitzy beach resorts never could. It wouldn’t just open up a new treasure trove of beautiful mountains for the world; it would drive local development. And it’d put down a financial incentive for the preservation of Bedouin knowledge about the mountains. Knowledge it took centuries to build up and which – once lost – could never be re-created the same again. Knowledge that shouldn’t just be seen as part of Bedouin cultural heritage; but as part of humanity’s heritage at large.

The Bedouin have always supplemented traditional livelihoods by guiding travellers in their lands; from traders to pilgrims and early explorers. Mountain tourism like hiking – which has proved so successful in other Arab countries – would be a sort of modern re-incarnation of that, creating a type of work that plays to natural Bedouin strengths in a way the Sinai’s glitzy beach resorts never could. It wouldn’t just open up a new treasure trove of beautiful mountains for the world; it would drive local development. And it’d put down a financial incentive for the preservation of Bedouin knowledge about the mountains. Knowledge it took centuries to build up and which – once lost – could never be re-created the same again. Knowledge that shouldn’t just be seen as part of Bedouin cultural heritage; but as part of humanity’s heritage at large.

My plans for the future are to carry on hiking in the Sinai. There are still new mountains I want to do. And old ones I want to try new ways. And I’d encourage anybody who’s in two minds about going to the Sinai to visit too.

The mountains of the Sinai and amazing and safe to visit in the South. If you don’t want to go alone, small hiking groups have been active for years. New ones are springing up too, run by Egyptians and foreigners. I’ve seen more hikers in the mountains this year than any previous one too. It’s all grounds for hope; a sign things might be going in the right way. Once people start walking more in these mountains; going deeper and bringing their stories back it’ll become clear that Egypt isn’t just the equal of Arab neighbours like Yemen, Oman and Morocco when it comes to mountains. But that it’s the equal of anywhere in the world. And perhaps then – when the epic potential of these mountains becomes clear – it’ll be the base for more change and development.

THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN EGYPTIAN STREETS. Check out their website HERE and like their Facebook page HERE!

A couple of days ago, I was sitting in a cafe in St Katherine, sipping a cup of tea when big, Biblical thunder began echoing around. I walked outside to see what was happening and saw dark thunderclouds gathering over Jebel Abbas Basha – one of the big mountains near the town – and then smelt the scent of rain, carrying in the breeze. Over Jebel Abbas Basha the clouds burst, the heavens opened and a deluge fell; soon, the water level rose and a flash flood went tearing down through Wadi Shagg, on the western side of the mountain. Then, down to more distant wadis. People who saw it – including a Bedouin guide who was in Wadi Shagg with two foreign hikers at the time – said it looked incredible; a huge, raging river of sand, boulders and dead shrubs.

A couple of days ago, I was sitting in a cafe in St Katherine, sipping a cup of tea when big, Biblical thunder began echoing around. I walked outside to see what was happening and saw dark thunderclouds gathering over Jebel Abbas Basha – one of the big mountains near the town – and then smelt the scent of rain, carrying in the breeze. Over Jebel Abbas Basha the clouds burst, the heavens opened and a deluge fell; soon, the water level rose and a flash flood went tearing down through Wadi Shagg, on the western side of the mountain. Then, down to more distant wadis. People who saw it – including a Bedouin guide who was in Wadi Shagg with two foreign hikers at the time – said it looked incredible; a huge, raging river of sand, boulders and dead shrubs. This was my first time being near summer rain in the Sinai and I was annoyed to have not actually seen it. The next day I went to Wadi Shagg to see what it had left behind though. Everything looked beautiful. Red rockpools lay between the boulders, with small waterfalls between them. The sound of running creeks echoed around the sides of the wadi. The tracks of birds covered big, shining flats of mud – which were rippled like waves – as they dried slowly in the sun. Dead shrubs sat on top of boulders…

This was my first time being near summer rain in the Sinai and I was annoyed to have not actually seen it. The next day I went to Wadi Shagg to see what it had left behind though. Everything looked beautiful. Red rockpools lay between the boulders, with small waterfalls between them. The sound of running creeks echoed around the sides of the wadi. The tracks of birds covered big, shining flats of mud – which were rippled like waves – as they dried slowly in the sun. Dead shrubs sat on top of boulders… Quite apart from making these wadis look beautiful and giving brilliant canyoning-type adventures this rain is good news because the Sinai really needs it. Wells and springs are getting lower and everything is dry. Right now, in Wadi Shagg, tree roots are submerged in water and the animals have a place to drink. And it wasn’t just Wadi Shagg. Two other mountains – Jebel Tarbush and Jebel Serbal – also had rain. The Bedouin say more might be on the way this summer too. If you want to escape the heat of Cairo – or Dahab or Sharm – there’s nowhere better than Wadi Shagg. I reckon the waterfalls will stay a couple of days and bigger pools over a week. Just remember to look out for another flood. You never know, lightning might strike the same wadi twice…

Quite apart from making these wadis look beautiful and giving brilliant canyoning-type adventures this rain is good news because the Sinai really needs it. Wells and springs are getting lower and everything is dry. Right now, in Wadi Shagg, tree roots are submerged in water and the animals have a place to drink. And it wasn’t just Wadi Shagg. Two other mountains – Jebel Tarbush and Jebel Serbal – also had rain. The Bedouin say more might be on the way this summer too. If you want to escape the heat of Cairo – or Dahab or Sharm – there’s nowhere better than Wadi Shagg. I reckon the waterfalls will stay a couple of days and bigger pools over a week. Just remember to look out for another flood. You never know, lightning might strike the same wadi twice…