August 23, 2015

Bedouin navigation in Sinai

The Sinai has a reputation for being tricky to navigate. It’s the spot Biblical legend has it Moses got lost for forty years. History books report pilgrim caravans disappearing in the wilderness. Monks from the Monastery of St Katherine have gone wayward on mountain trails in recent times, as have hikers and inexperienced tour guides (who shouldn’t be guides at all). I often hear the Sinai described as a maze or a labyrinth (never by the Bedouin, always by outsiders) and I’ve heard people wonder awestruck at how the Bedouin navigate it, as though they must be possessed of a navigational sixth sense. At times, with the best Bedouin navigators, it can feel like they do have a sixth sense; but I’ll try and demystify exactly what that is in this blog post and how they do it.

The Sinai has a reputation for being tricky to navigate. It’s the spot Biblical legend has it Moses got lost for forty years. History books report pilgrim caravans disappearing in the wilderness. Monks from the Monastery of St Katherine have gone wayward on mountain trails in recent times, as have hikers and inexperienced tour guides (who shouldn’t be guides at all). I often hear the Sinai described as a maze or a labyrinth (never by the Bedouin, always by outsiders) and I’ve heard people wonder awestruck at how the Bedouin navigate it, as though they must be possessed of a navigational sixth sense. At times, with the best Bedouin navigators, it can feel like they do have a sixth sense; but I’ll try and demystify exactly what that is in this blog post and how they do it.

There are a few things to say at the start. Firstly, although the Bedouin know the Sinai better than anybody in the world, they don’t all know it. The ones who know it exceptionally well and the best navigators are a small minority.

Most Bedouin know the Sinai averagely well at best (but it’s important to say this is still significantly better than the vast majority of outsiders).

It’s also important to say it’s still a lot better than most younger Bedouin. Many Bedouin – especially those under 30 years old – know the Sinai much less well than the generations that went before them. Many of the younger Bedouin would get lost if they walked far today and I’ve been with some who have done exactly that, relying on their camels to guide them the remainder of the journey (camels, incidentally, are all-too-often unfairly denigrated creatures with an incredible memory of routes they’ve walked in the Sinai, but this is another story).

That’s the reality of Bedouin life in the Sinai today. Most Bedouin – especially the younger generations – live in a more modern world where knowledge about how to navigate – as well as knowledge on how to use plants for food or medicine or to track animals or even knowledge about their tribe’s own heritage and history – is becoming increasingly irrelevant to life and thus forgotten.

The 21st century is the great age of attrition for Bedouin knowledge.

Second, it’s important to say that – even with the most knowledgeable of Bedouin navigators – their knowledge is usually confined to their own tribal territory. Take them to the territory of another tribe and they’ll know it much less well. A tribesman of the Jebeleya tribe from St Katherine won’t know the lowlands of the Tarabin tribe half as well as he knows his own high mountains. He may know the main wadis and mountains of the Tarabinian lowlands and may be able to navigate these but he’ll certainly miss a lot of the detail in between. This plays out on a smaller scale too. Often Bedouin will know a specific part of their territory – such as the one where they grew up – better than other parts.

Most Bedouin navigation – at least in South Sinai – is done from memory.

The Bedouin grow up walking; they walk with their parents, then increasingly on their own or with friends seeing the same landscapes repeatedly over many years and developing a deep familiarity with their small details and secrets. Over the years they build up an exceptionally rich mental picture of their territory; of what’s where and how to get there. Its mountain peaks, wadis and basins all act like gigantic reference points. These never change: they remain constant signs and waymarks for a Bedouin finding his way. Similarly, smaller, permanent signs in the landscape – a rock, or a fig tree; or a mark in a cliff – give more subtle reminders about where to go, where to turn etc.

The Bedouin grow up walking; they walk with their parents, then increasingly on their own or with friends seeing the same landscapes repeatedly over many years and developing a deep familiarity with their small details and secrets. Over the years they build up an exceptionally rich mental picture of their territory; of what’s where and how to get there. Its mountain peaks, wadis and basins all act like gigantic reference points. These never change: they remain constant signs and waymarks for a Bedouin finding his way. Similarly, smaller, permanent signs in the landscape – a rock, or a fig tree; or a mark in a cliff – give more subtle reminders about where to go, where to turn etc.

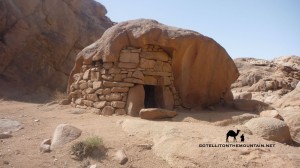

Sometimes, in places where navigation is tricky – e.g. a rocky, sandy areas across which there is no path – the Bedouin build trail marking stones called rojoms. You can see one rojom from the next, following them in a line through the difficult section. The best navigators won’t need these rojoms but they’ll be extremely valuable to the Bedouin who know the landscape at best averagely well. Following these is just like following a path (and of course there are plenty of paths in the Sinai, some of which are easier to follow than others, but all of which simplify navigating the mountain landscape considerably).

What about ways the Bedouin use to navigate indepedent of memory though? Independent of what they know from the ground itself?

In some parts of the Middle East the stars were key to Bedouin navigation, including parts of North Sinai. Here the stars and sometimes the horns of a crescent moon were important for navigating at night. Two stars were of special significance: Polaris (which the Bedouin call Al Jidi) and Canopus (which they call Suhayl). You’ll often hear references to these – and how they were used for navigation – in poems and stories. Polaris was a constant guide to north, visible all night, all year, whereas Canopus – which indicated south – was less constant; it wasn’t always visible and when it was it’d often remain on show just a couple of hours. But this was mostly in North Sinai.

Things were different in South Sinai. I’ve never seen a Bedouin use the stars in the south and although many older Bedouin will know how to find north and south from the stars I’ve only heard of the stars being used to find the way here in the most exceptional of places and circumstances.

There are several reasons why North and South are different in this respect.

Generally, the stars are best for navigation in landscapes that can change – e.g. vast sandy deserts like the deep Sahara, where the wind can alter the shape of dunes, cover rocks and outcrops and blow any trails away. Or in landscapes that look the same; ones that are bereft of good landmarks and where it’s difficult to distinguish one part from the next, such as plains and low dunes common in North Sinai. The visual appearance of the land or at least human judgement of it can’t be taken as a good enough indicator of the way to go in these places which forces us to look outwards for other, more constant elements that give us more reliable guidance, like certain stars.

Generally, the stars are best for navigation in landscapes that can change – e.g. vast sandy deserts like the deep Sahara, where the wind can alter the shape of dunes, cover rocks and outcrops and blow any trails away. Or in landscapes that look the same; ones that are bereft of good landmarks and where it’s difficult to distinguish one part from the next, such as plains and low dunes common in North Sinai. The visual appearance of the land or at least human judgement of it can’t be taken as a good enough indicator of the way to go in these places which forces us to look outwards for other, more constant elements that give us more reliable guidance, like certain stars.

That’s different to South Sinai though. Unlike the North, this is chiefly a landscape of mountains and stony, rocky deserts with outcrops. It has a rich supply of markers that remain unchanging between the generations and which are ample to guide any good Bedouin navigator where he needs to go.

The Bedouin of South Sinai would have about as much reason to use the stars to navigate as a resident of Cairo would going between Zamalek and Maadi.

Simply, it’s unecessary. Better, easier things tell you the way.

Navigating with the stars also has serious limitations in a landscape that’s as intricate as South Sinai. Navigating here isn’t simply about identifying north and going for it in a straight line, like it might be in open deserts or plateaus or out on the sea. Big mountains get in the way in South Sinai. There are deep wadis to cross. There are high cliffs you can fall off. In landscapes like this the stars and the moon are more useful for the light they can throw over the landscape when they’re shining brightly rather than the directions they indicate. Getting through places like this is about micro navigating the intricate terrain of the mountains on routes that are winding, tricky and difficult to follow.

When I hear people say the Bedouin use the stars to navigate in South Sinai – especially now, in the 21st century – I know that i) either they know very little about the Sinai or the reality of navigation in it or ii) they do but they push this myth anyway because it sounds romantic and plays into outsiders’ – and especially Western outsiders’ – fantasies about who the Bedouin are and how they live that for whatever reason they want to capitalise on; it makes them sound exotic, with magical, esoteric skills, and an air of oriental mystique. I see this orientalising drive in bad travel writing and dodgy full moon party ads about the Sinai and – as appealing as it is to the imagination – the bulk of it isn’t true. Today, the reality is that many Bedouin – including some of its best navigators – are people who listen to mp3s, have smartphones and Facebook accounts; they watch TV shows, download stuff off the internet and spend hours on YouTube. And indeed why shouldn’t they? Why should this make them less Bedouin? Why should we maintain a description of the Bedouin that outsiders find romantically pleasing but which is out of date (assuming it was ever accurate at all)? Describing them in a more accurate and up-to-date way bursts the romantic vision many have but perhaps that isn’t a bad thing.

Up until now then it’s clear that – in South Sinai – the Bedouin navigate chiefly by getting to know specific areas exceptionally well; by building up a very rich mental map over many years that out-competes what anybody else could have and recognising the signs that mark the way.

It all sounds very visual and most of the time the vast bulk of it is.

Perhaps what sets the very best Bedouin navigators apart is their ability to use other senses – ie senses apart from sight – to know the way. Sometimes, this is necessary; especially in the high Sinai mountains, which can be hit by poor weather. Sometimes, mist and cloud whip across the mountains, reducing visibility; even so, visibility is very rarely so poor that a Bedouin navigator wouldn’t be able to see what was needed to make judgements about where to go. The worst conditions I’ve seen in the Sinai were on top of Jebel Katherina in freezing weather at night when visibility was just a few metres ahead.

Weather like this makes navigation much more serious. It makes it harder and it introduces a more unknown element into the equation which can spook some people and lead them into making bad decisions.

Nevertheless, a good Bedouin navigator would still be able to get through this. He will be slower; he will need to think and focus more, but the very best will nevertheless be able to deal with it and find his way through.

So how does he do that if he can’t see where he’s going?

Again, it all comes back to that exceptionally rich mental map a Bedouin has of a particular area: without sight, he needs to rely on other senses to interpret that map and locate his position on it. Whilst he might not see the ground he’s standing on, as he moves over a mountainside he’ll be able to feel the contours of the slope he’s on with his feet and balance: he’ll be able to feel where it gets steep and where it becomes flat; similarly, where it gets smooth, or rough, or where he walks onto scree. Each of these pieces of information is key and he will be able to use them to locate himself and proceed correctly. If you closed your eyes in your house and focused, you might be able to slowly find your way to the bedroom, feeling your way, using the same basic principles. It would’t be as easy as doing it with your eyes open, but it would be possible.

As well as the sense of touch the best navigator – again through his experience of having walked these landscapes so many times will have a sense of distance and timing built into his mental map. He will know how long it takes and feels to walk from one part of it to the next, even when doing it more slowly – for example in bad weather – and will be able to get a sense of where he is.

These techniques are similar – if less formal and exact – to the ones we’d use in the West to navigate in low visibility conditions.

When you wonder how the Bedouin navigate the Sinai – and I mean South Sinai here – remember, it’s chiefly about an extremely rich mental map. It’s about building up that map over many years and being able to interpret it intelligently through different senses as required. The way the Bedouin seem to ‘know’ the way even in the night or difficult weather might seem magical: but I hope this shows a bit of how it’s actually done. As for how outsiders in the Sinai, for all but the most experienced navigators you’ll generally need to use other methods (guidebooks, maps, GPS, Google Earth or a combo of these). Really though, the best plan is to use one of the best Bedouin guides/ navigators; because when you really need them, they are about as good as it gets keeping you safe through the Sinai. Nothing else comes close.

When you wonder how the Bedouin navigate the Sinai – and I mean South Sinai here – remember, it’s chiefly about an extremely rich mental map. It’s about building up that map over many years and being able to interpret it intelligently through different senses as required. The way the Bedouin seem to ‘know’ the way even in the night or difficult weather might seem magical: but I hope this shows a bit of how it’s actually done. As for how outsiders in the Sinai, for all but the most experienced navigators you’ll generally need to use other methods (guidebooks, maps, GPS, Google Earth or a combo of these). Really though, the best plan is to use one of the best Bedouin guides/ navigators; because when you really need them, they are about as good as it gets keeping you safe through the Sinai. Nothing else comes close.